Introduction to Kalarippayattu

#WednesdayWisdom is a series that began during the 40th anniversary celebration of Akademi to revisit Indian classical dance roots by sharing gems of knowledge from ancient Shastras (dance texts) that hold relevance even today. The blog is curated by Bharatanatyam artist, Suhani Dhanki, along with with our Head of Marketing, Antareepa Thakur.

In this blog series, we are inviting artists practicing different South Asian dance styles to contribute some interesting facts about their art forms, some of them rarely seen in the UK. Read our previous blogs in this series here.

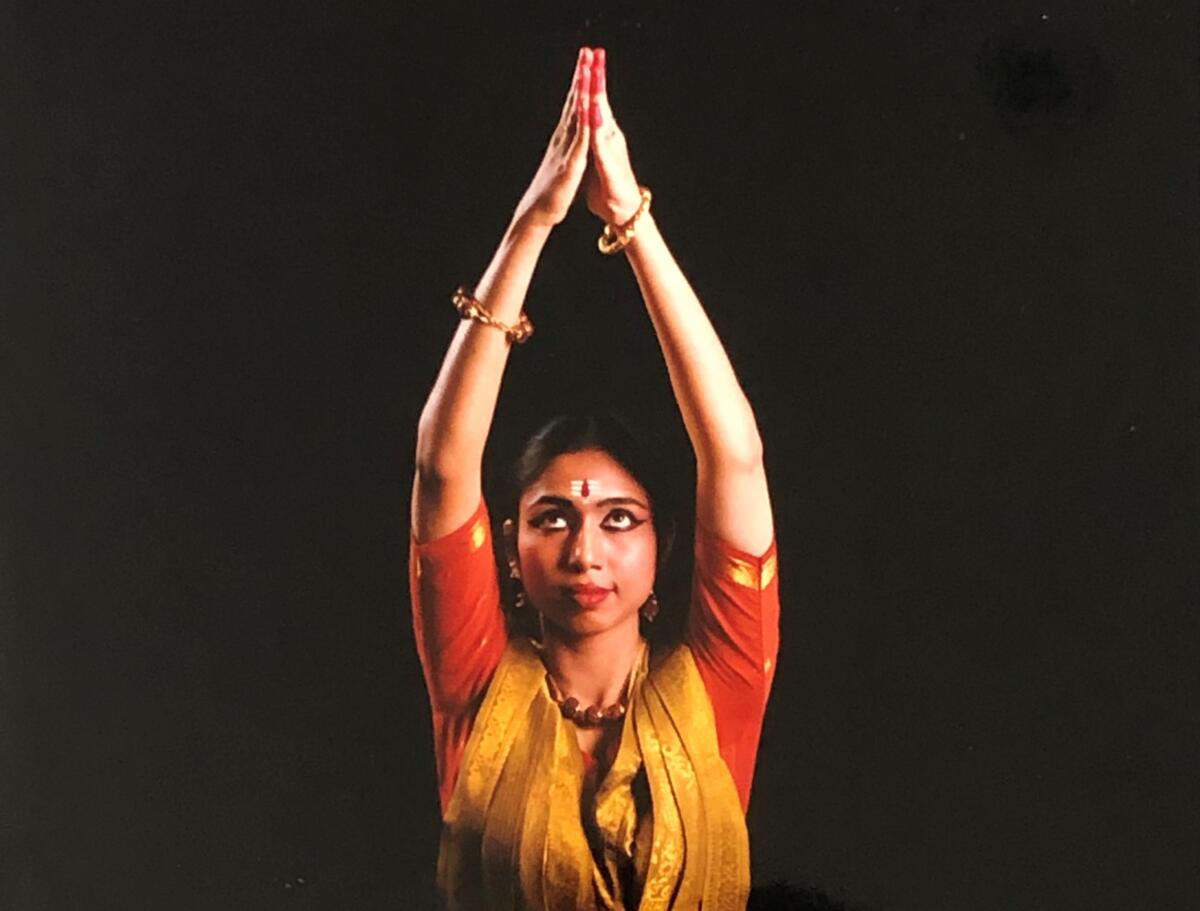

This blogpost on Mudras in Kalarippayattu is researched and written by Geetha Sridhar, a Bharatanatyam artist and teacher who has also trained in Kalarippayattu, with the two art forms informing the other in her practice. In this article she explains the mudras in Kalarippayattu and compares the art form with Bharatanatyam.

Kalarippayattu, a self-defence artform that has its origins in Kerala, South India, is one of the most ancient martial art techniques that is still in existence. The word Kalari, indicates ‘institution’ and Payuttu means ‘imparting’. Epistemological evidence found in the Dhanurveda of the Upavedas traces it back to 3rd century BCE. Legend has it that Lord Parasurama (sixth incarnation of Lord Vishnu), chose men of upper caste who belonged to subsects of Ugram Valli, Dronam Valli, Khoram Valli and Ullur Thuruthiyad and imparted the nuances of warfare to them. This created a lineage of practitioners and eventually 21 kalaris were established by the chosen 21 experts and thus multiplied further. Kalarippayattu is an umbrella term that covers a methodical training in philosophy, healthcare, physical training and martial technique.

Bharathanatyam is an Indian classical dance form that also has its origins in India, indigenous to the state of Tamil Nadu. It dates back to 2nd century AD. The most commonly used explanation for the revived term of ‘bharathanatyam’ draws upon the first syllables of three words, that encompasses the essence of the style, namely; Bha from bhavam (mime), Ra from Ragam (music) and Tha from Thalam (rhythm) and Natyam translates as dance.

As a Bharathanatyam dancer, having trained in Kalarippayattu (mainly as a co-existing discipline to enhance and hone my dance skills), I draw upon some parallels and comparisons in analysing the use of Mudras in their respective physical disciplines.

Similar to classical dances of India, Kalarippayattu follows a strict structured method of learning vocabularies that progressively lead on to a finer exposition of the art of warfare. Whilst there is evidence of existence of the art of warfare in ancient times, Kalarippayattu follows no text, as Indian classical dances do with the Natyashastra. The teaching and learning in Kalarippayattu is more an oral tradition as in Guru-Sishya parampara, which predominantly is the case with Indian classical dances too when it comes to learning the physical vocabulary of the respective styles. However, with dance, there is an unshakeable foundation when it comes to the theatrical aspects that one follows through the Natyashastra even today. The vast codification in the text include, narratives, symbols and dialogues.

A distinctive feature that Natyashastra addresses in the second chapter is the norms of theatre architecture. Likewise, Kalarippayattu is highly disciplined in adhering to the ritualistic practice of establishing both an architected practice space and consecrating the appropriate deity of worship in that space. The dimensions of the space are well calculated according to the vasthu sastra. A unique feature here, is that the space is carved out by caving into the earth’s surface. This is called Cherukalari or Kuzhikalari. A sanctum called the Poothara, which is a seven stepped arc is created in the south west corner in a Kalari that is worshipped by every practitioner of Kalarippayattu. The other conventional deities are Lord Ganesha and Nagadeva. (serpent god). This is very comparable to a deity of Nataraja and Ganesha that Bharathanatyam dancers’ worship both in their classes and on stage. However, the other directions (north west corner, north east corner, and south east corner) are taken into consideration and dedicated to gods and goddesses or war and weaponry in a Kalari.With particular focus on the mudra aspect in the two disciplines of Bharathanatyam, and Kalarippayattu, I would say that it is an imbalance of the former being more abundant in its usage and the latter being quite frugal. As with Bharathanatyam, Kalarippayattu also has an invocatory ritual of doing the Namaskaram called the Poothran Vandhanam. There is far more usage of mudras in this sequence. It involves mudras such as pathaka, Anjali, Kapotha and Alapadma. The intended meaning also displays the same idea of gathering flowers to be offered as in bharathanatyam.

As regards Bharathanatyam, it has easy access to the Samyuktha hastas and Asamyutha hastas that form the basic manual with which to denote things. With some of the mudras we can easily see the connection of its exposition from the shape or pattern that is created using our fingers. For example, sarpa shirasthatha, of the single hand gestures or nagabhandhakaha of the double hand gestures don’t need explanation as to what are depicted. The bend in the tip of the fingers is an uncanny semblance of a snake’s head. Whereas, with Tripathaka or ardhapathaka, which translates as half a flag or three quarters of a flag, is not instantly decipherable. In that instance, usages or viniyogas of such mudras are far more expressive when they are used to denote various things such as fire (Vanhijwalavi grumbhanae) with tripataka mudra or dwaje (flag) with the ardha pathaka mudra.

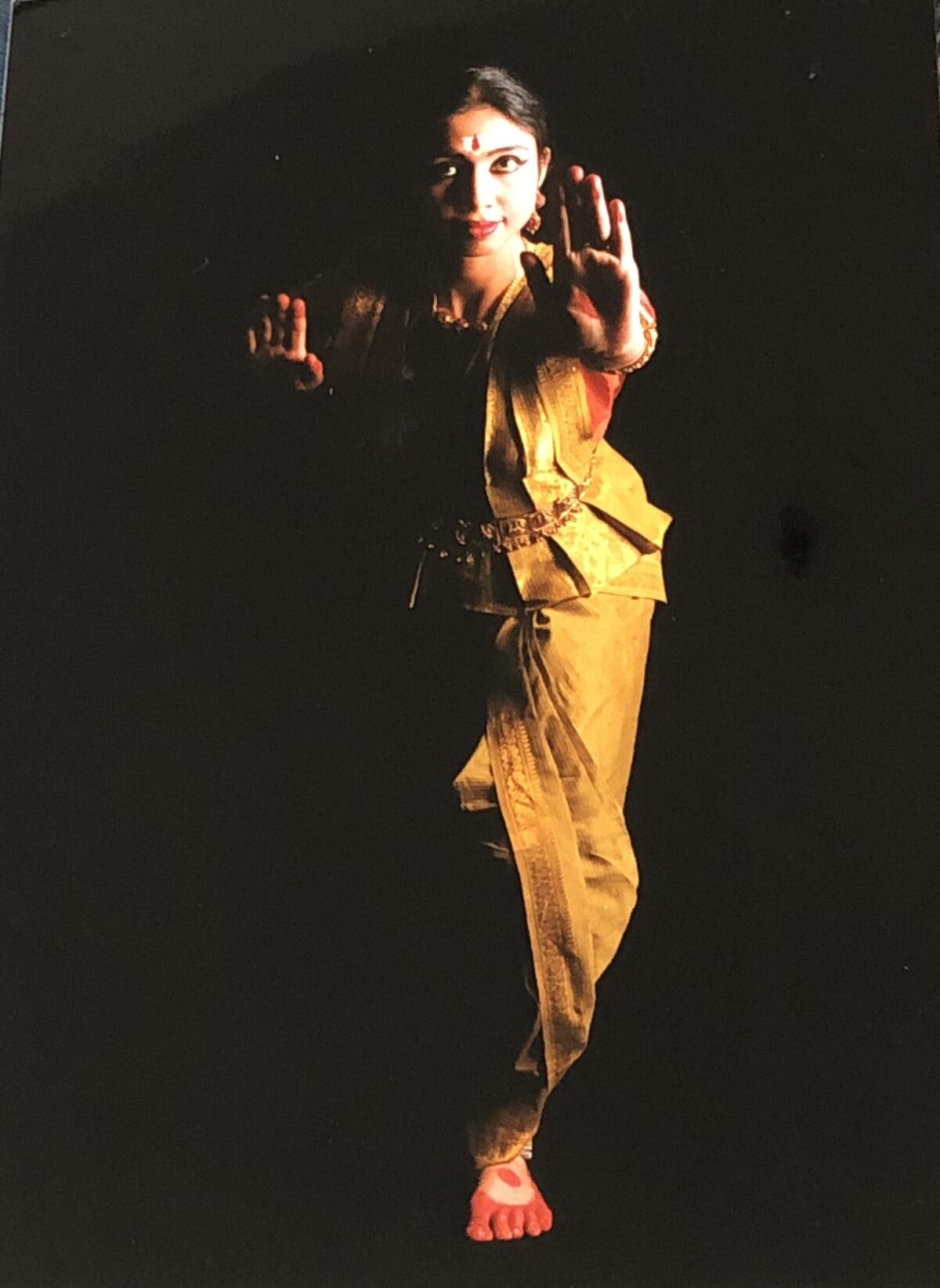

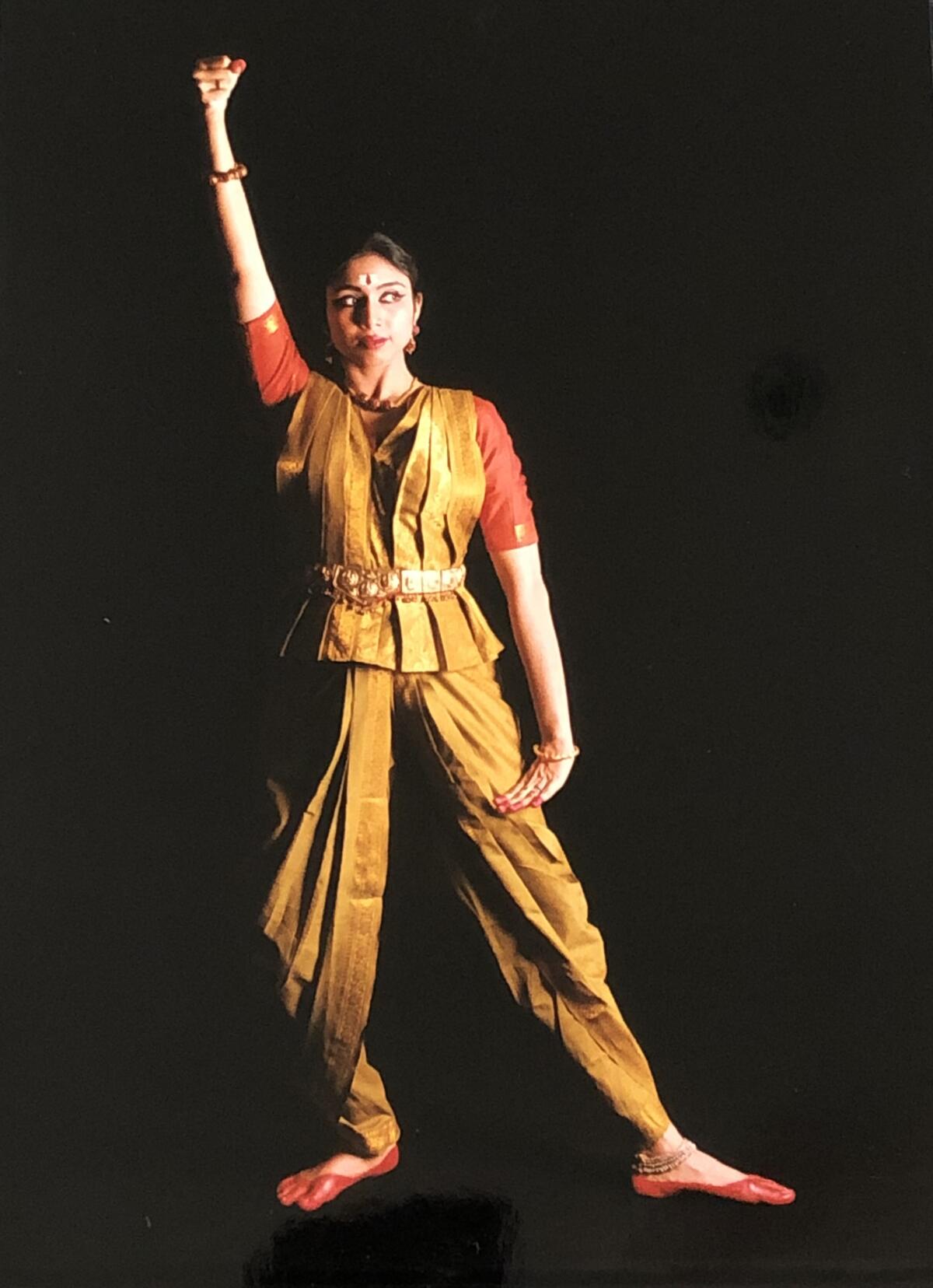

The role of mudra is very minimal when one learns the basic body conditioning exercises called the Meyyirakkam in Kalarippayatu. Further in the training, in understanding stances or Chuvadu, and in executing movements, or Vadivu, whilst the arms are held in specific position, the hands don’t hold any specific mudra of clarity. They assume a natural unintended pathaka hasta in most cases. Specific mudras come into light in adapting the Vadivukaal or the choreographed eight positions in Ashtavadivu.

Each of these postures are associated with a bird or an animal as they are assumed for the purpose of self-defence. They are Simha, Gaja Ashva, Sarpa, Marjara, Varaha, Kukkuda and Matsya.

- Simha: Lion, uses Vyagraha mudra that is used to denote a tiger/lion in bharathanatyam

- Gaja: Elephant, uses both hands in shikaram resting on the kundalini point.

- Ashva: Horse, uses both hands in pathaka with elbows crossed over at the chest.

- Sarpa: Snake, transmits from Anjali to pathaka.

- Marjara: Cat, uses Vyagraha in both hands and grasps the earth in a parshwasoochi-like position called Pandhittuamarnu.

- Varaha: Pig, uses a similar mudra as in karkata, but clasped tightly.

- Kukkuda: Cockerel, uses swasthihasta, but crossed over closer to the ears.

- Matsya: Fish, is depicted in eka pada with the upper body bent forward with one arm extended forward in pathāka and the other arm held behind also in pathāka.

The other mudras that are used in fighting are Mushti and Agni. In these applications, the mudras are neither decorative nor meaningful, but it is an active part of the attack and defence tactic.

Interestingly, similar terms are used in demonstrating the pāda bedās (stances) in both disciplines. To name a few some such are Āleedam, Prathyaleedam and Samapadham. When it comes to Vaachika aspect, Vayitthari or commands are spoken in the language of Malayalam to take a stance or perform a movement in Kalarippayattu and Sollukattu or rhythmic syllables are recited in performing a dance phrase in bharathanatyam, alongside using a range of musical instruments and Carnatic music. Some schools of Kalarippayattu follow concepts of Shiva and Shakthi in their training of Meypayattu as the linear and circular movements as parallel to the perceptions of Tandava and Lasya in bharathanatyam.

The similarities in some of the aspects of the two styles are not only apparent but also fascinating for a choreographer. Chandralekha, a pioneer in Indian Contemporary dance stands at the forefront in having identified the compatibility of the two disciplines and has explored the possibilities of juxtaposing and mutualising them in many of her works. Though I am tempted to go on about these collaborative works, I shall leave it here for the moment as it is a whole new topic on its own.

Credits: I thank Brandy Leary for consultation on technical aspects of Kalari.

References: ‘Kalarippayattu’ – P. Balakrishnan (1995)

Watch this space for more blogposts in our #WednesdayWisdom series.